76ers Musings: Embiid’s injury, moving forward, and the future of analytics

When news came down that Joel Embiid would miss the remainder of the season due to complications with a torn meniscus in his left knee, the reactions were swift.

Panic was, by no means, an unexpected response. This was a player with serious long-term injury concerns in the form of both back and foot injuries. The brightest of talents who has will miss 215 out of a possible 246 games to start his NBA career. That number alone is staggering.

Panic is also expected because of what Embiid was able to show in the 31 games he did play, and how we, as Sixers fans and media, adjusted our expectations because of them. I frequently said in the offseason that once Embiid begins to play, we’re going to be even more worried about a possible injury because he was able to show us what he’s capable of. After averaging 20.2 points, 7.8 rebounds, 2.5 blocks, and 2.1 assists per game, while showing his prowess as one of the best defensive big men in the NBA, we are now keenly aware of the talent that can be ripped away from a fan base that embraced Embiid with little hesitation.

While that emotional response is predictable, and has somewhat died down over the last week, is the meniscus tear that will shelve Embiid for the rest of the season something to worry about long term?

I first want to be clear on what exactly it is I’m debating. I’m not questioning whether Embiid is a serious injury risk going forward. He is. But that risk exist because of the stress fracture in his back he suffered while at Kansas. Present because of the navicular bone he’s needed two surgeries to repair. My question is whether the meniscus tear is something to be concerned with long term, whether it proves anything about Embiid’s durability, and whether it changes the probability Embiid will remain healthy going forward.

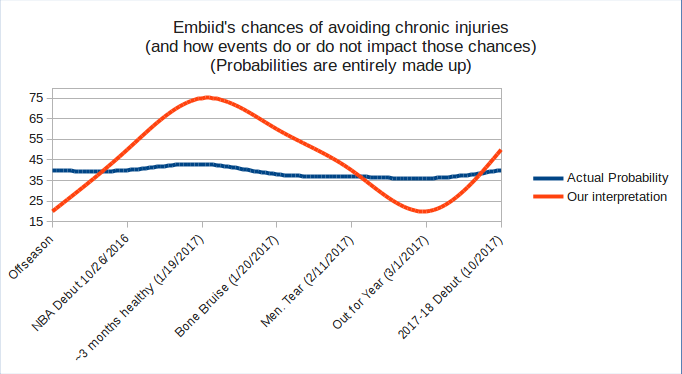

I suppose a fake graph would be an easy way of describing what I’m talking about. Below is a graph where I’m trying to guestimate what the probability would be of Embiid staying healthy throughout his career. Not in a “he’ll never have bumps and bruises” kind of way, but in a “avoiding chronic injuries that threaten his career” kind of way.

In this graph I set a baseline, then estimate (completely made up, on the spot, unscientifically) how the events of the last 7 months have impacted this probability. The orange line is how I believe we, in the media and as fans, interpret the probability changing at each stop along the way. Again, completely made up on the spot. I’m just trying to explain a tendency, not get a scientifically accurate forecast.

I feel as if we had a false sense of security earlier in the season, security which only grew when Embiid played a couple of setback-free months, and security which became shattered once a freak landing resulted in a relatively common, and short-term, injury.

Missing 215 out of a possible 246 games to start his career looks really, really bad. And, to be fair, it is. But that perspective is painted almost entirely by the navicular bone which caused him to miss his first two seasons. When you isolate the new information, and how that impacts his future health, this meniscus tear isn’t likely to be a big factor down the road.

It’s an injury that looks bad because of the previous two seasons. That looks bad because he’ll end up missing 51 games this year, even though that number is heavily influenced by the team’s cautious approach to bringing him back, as Embiid missed 11 games prior to the January 20th injury, through little fault of his own. It’s a number that looks big because of what appears to be a misdiagnosis at the beginning, because the team has little to play for at the end of the season, and because it continues to behoove the Sixers to be as cautious as possible with their franchise player. None of these speak to the severity of the injury or its likelihood to be problematic down the line.

If this were the navicular bone, you should panic. If this were the stress fracture in his back, suffered while at Kansas, acting up once again, you should panic. If this were a Jones fracture, or even an ACL or an MCL, you should be more concerned about his long-term durability. This was a very minor injury likely caused not by the wear and tear of an NBA season, but by a freak landing. To be honest, when I watch that play even now, a torn meniscus seems like the best case scenario.

Once again, none of this is to paint Embiid’s health as anything close to a sure thing going forward, just that the meniscus tear doesn’t move the needle all that much.

Prior to the team’s announcement that Embiid would miss the remainder of the season, Sixers fans were of the mindset that the team should take a cautious approach with their superstar. There’s nothing to play for, and Embiid’s long-term health is more important than anything they can accomplish this season. Then the team takes the cautious approach and … panic.

There are a lot of reasons to be frustrated at how the last 6 weeks have gone down. The decision to put Embiid back into the Portland game after landing the way he did. The decision, which still makes zero sense for a team supposedly as cautious as the Sixers are, to play him in Houston. The misdiagnosis of the cause of the swelling. Bryan Colangelo’s indignant response to anyone who dared question whether something else was going on.

The real problem with the meniscus injury isn’t what it means for Embiid, whether it will be a problem long-term, or whether it proves he is incapable of withstanding the grind of an NBA season. The real problem is that it reminded Sixers fans something we had spent half a season repressing in our mind: this can all be taken away in a fraction of a second.

Adam Silver on championship or bust

NBA commissioner Adam Silver set off a debate over the weekend when he stated, while at the Sloan Sports Analytics Conference, that “it’s irrational to run your team as if the only thing that matters is a championship.”

The response on twitter was interesting, if for no other reason than because of how varied the responses were, with equal parts “finally somebody gets it” mixed with “how is that not the goal of professional sports.”

When you mix in the rumors that the NBA had a role in forcing the Colangelo’s on Philadelphia, and the reaction in the Delaware Valley was as expected.

There’s some validity to the argument Silver is making, which in full context was how bad the side effects would be for fans if 20 teams operated under that narrow lens. Yet that would never happen, since if 20 teams pursued the same strategy the odds of executing it successfully would drop precipitously.

The real response, rather than telling his teams how they should be run, is to fix the competitive balance issues at the heart of the matter. Want to prevent teams without a superstar from tearing it down completely? Increase the likelihood that middling teams without a superstar to make them a destination can acquire that first franchise-defining player. Increase the usefulness of cap space. Force teams into making real decisions to retain their collection of star players by giving them real consequences to doing so.

Yet CBA after CBA the NBA continues to add incentives to make sure teams have every opportunity to retain the few players in the league actually capable of turning another franchise around, coming to a crescendo with the new designated player exception that will shape the marketplace when the new CBA comes into effect July 1st.

The NBA, and the media, like to talk about how winning a championship isn’t everything. Yet since Daryl Morey took over the Houston Rockets starting with the 2007-08 season, the Rockets have a 467-319 (59.4%) record over that span, the 2nd best record in the NBA during that time. He has had 0 losing seasons in his 10-year tenure.

Yet when the Rockets struggled to a 41-41 record last season, even after going a combined 110-54 in the previous two years, Morey was on the hot seat, with speculation that it was time to move on. 2nd best record in the NBA over what was then a 9 year run. No losing seasons. A conference finals appearance. Yet none of that mattered in the court of public opinion because Houston never won the ultimate prize.

That’s what gets me about all this misdirected anger. Yes, it would be great if the league’s incentive structure didn’t make tanking a viable, and rational, strategy. But the solution to that problem isn’t suggesting that GM’s pursuing a win-at-all-costs strategy are wrong in doing so. That is the curve history will grade them on, that is the criteria fans will revolt against if not met, and that is the noise that will cause owners to feel pressure to make a move. Let’s not kid ourselves here.

Luis Scola makes sense of analytics

“Analytics don’t have to be perfect,” Luis Scola said on a panel during last week’s Sloan Sports Analytics Conference. “Nothing can be perfect. You’re just looking for better than before.”

It’s such an obnoxiously simple concept, yet it’s one that needs to be stated over and over and over again. Any time somebody is anti-analytics they’ll always look for the outlier, the example or two that are somehow meant to “disprove” the usefulness of a metric, or of analytics as a whole.

It’s a level of scrutiny we apply to almost nothing else in life, and certainly not in this sport. Nobody is going to take a scouts draft board and, if he gets one projection wrong, say that scouting has no place in the league. Yet that’s what feels like happens when we talk about analytics.

I’ve frequently said that those who believe in using analytics are more skeptical towards numbers than those who don’t. There is nobody in the league, or who covers the league, that doesn’t use numbers to some degree, whether that’s field goal percentage or true shooting percentage, whether that’s rebounds per game or rebounding percentage, or whether that’s points per game or RPM or warp projections.

But where some people have settled on the well-traveled metrics like per-game stats, practitioners of analytics (the good ones, at least) are keenly aware of the weaknesses in the numbers they use, and are always on the lookout for ways to improve upon those weaknesses.

And if we’re not looking to constantly improve our methods of evaluation, whether that’s traditional scouting or with statistical tools, then what’s the point?

Related Posts

-

Aaron Stange

-

Oran Kelley

-

Derek Bodner

-

Eric Hines

-

Oran Kelley

-

Thomas Dauphan

-

-